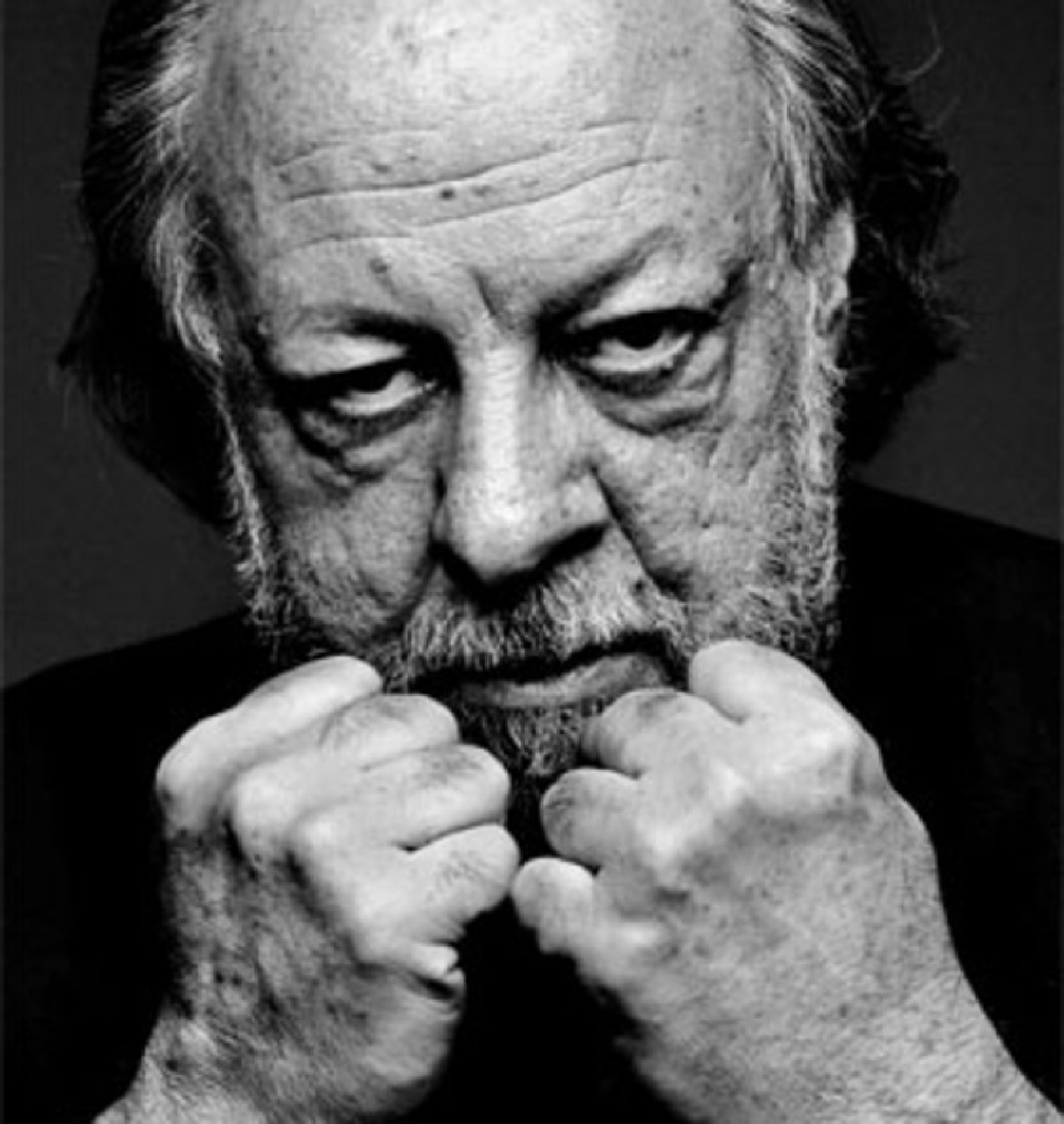

As a kid, I was creeped out by the magicians who acted as if they had ‘special powers.’ I wanted to be fooled by the tricks, not by the 1970s leotards and sequins. I wanted them to look like guys who could be working normal jobs or selling air conditioner boxes filled with bricks at the off-ramp by I-94 and Halsted.

Oh, Lucky Me

(for Ricky Jay)

10 years old he switched the Colgate

and Brylcreem, proud of the simple

subterfuge between cabinet and sink,

seeing the first signals of something

(that knowledge existed between gestures)

uncertain and disappointed to be

the son of obedient routine.

To learn how to see what others couldn’t

he sought out Catskills magicians with names

once chopped, rounded, and Americanized

by Ellis Island lines, names refracted

again balancing the urge to stand

apart and remain within the crowd.

To see how hands could move he sought out

Vegas sharps who performed in silence

with names meant to be forgotten.

He created séances of mirrors

to slow time between bright spotlight gestures,

watched his own hands from every angle

until they belonged to a stranger.

One morning he woke up ambidextrous.

He learned not to look at the ghosts of his

hands unless he wanted others to see.

He disappeared himself, looking for a

way to master that invisible gap

between people where each space signified

possible truth between words. He wanted

to find the gap where nothing happens and

nothing is said. He wouldn’t talk about

his parents, but his sister was okay.

I saw him first at a card table

in a Mamet movie, lugubrious

and hooded when calling the last hand in

the United States of Kiss-My-Ass.

He said the lines right, dead bored and angry:

“What is this ‘marker’? Where are you from?”

Not stomping along with the beat, drumming

a bit ahead: “Who is this broad?”

or dragging behind: “Club flush. You owe me

six thousand dollars. Thank you very much.

Next case.”

Dismayed to see him giggling with talk show

hosts, I expected a stone-faced disruption of

the showbiz mutual non-aggression pact.

I wanted the Jungian shadow of

every magician, a criminal

carrying the fantasied grace and the

palpable rage of a child ignored

and a fake name so obvious it was

more real than birth.

He built his library and a thug took it --

dismissive of the cup-and-ball trick

depicted in hieroglyphics and the

history of the world infused with fools

or tricksters since the first owl-faced God

scratched on rock – a foreclosed car lot cleared

without a drop of sweat, just the brute force

of a world where math is not memory,

but the gravity of capitalism

where there is no illusion and no grace.

He held a bemused tolerance for the

year he was born and the years in which he

stood. The name discarded, a point of pride --

like being born in a car wreck.

Against that sadness, being outside time

was another trick to save himself.

A sold-out run at the Old Vic, the true

sharps never came backstage, but sat with their

new wives just off the center aisles.

He breezed through the differences between a

Vegas shuffle, a gin rummy shuffle,

and a child’s two-palmed scramble to always

find, as he said: “Oh, lucky me,”

the ace of spades yet again.

He quoted Seneca, Villon, and Shaw

between dead cuts, bottom and second deals:

“Every profession is a conspiracy against the laity.”

Audience members at each elbow he

made the queens and aces appear at will.

He simply knew where they were at all times.

A woman from the BBC told once

of his truculent participation

in documenting his own life,

(he refused to perform for her cameras)

making her job more difficult than it need be.

Lunch in LA, he chose the restaurant,

pissed her off all day, and then, as the

waiter took the laminated menus away

from the glaring sun of the corner booth,

made a block of ice appear between them.

She didn’t know why she burst into tears.

She asked: “Why did you do this to me?”

He shrugged: “I lie for a living.”

(originally published in Tuck Magazine, later published in Shadow Box)