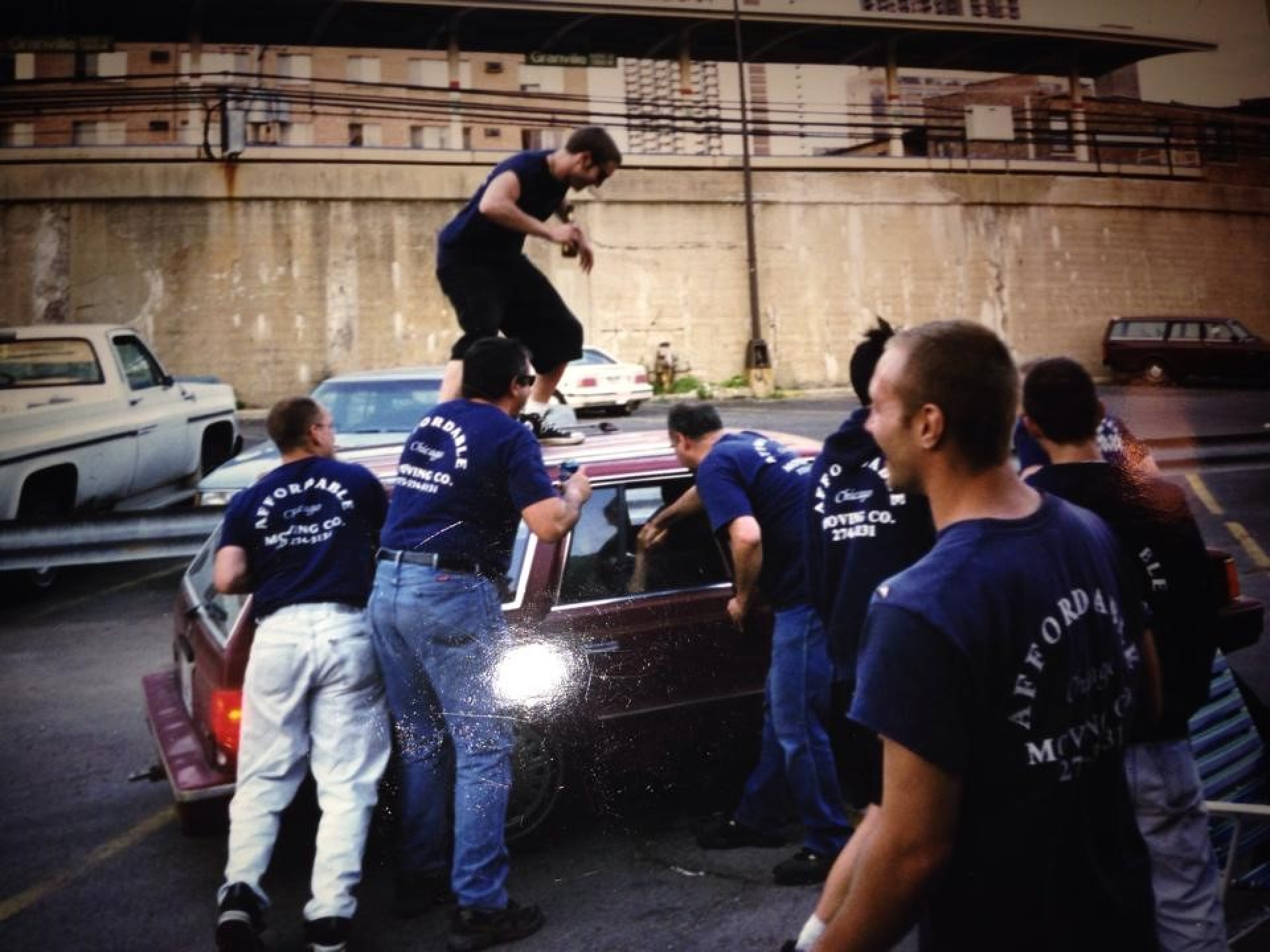

(This was an introduction to a re-printing of an old novel, The Heavyweight Champion of Nothing, about working class guys committing crimes to get back at their boss)

*

The motivation for most criminal acts can be summarized as: “I saw something I wanted, so I took it.” In general, people go to jail for two reasons: They do not consider incarceration a deterrent and/or they don’t believe they’ll get caught in the first place.

Jacques Mesrine, proudly classified as Public Enemy #1 in France and Canada fifty years ago, was willing to pay the price for what he wanted. Throughout his autobiography, which has to be taken with many grains of salt, he did frequently cite his wish to die rather than be denied. So he committed daylight bank robberies, sometimes twice a day; engineered prison escapes, once taking a judge hostage and another time, returning to the prison to prompt a gunfight at the gate; during one late-night apartment burglary in Paris where the safecracker’s drill broke, Mesrine went down the street and burglarized a hardware store for more drills and then returned to the first burglary in progress. Mesrine was the rare outlier as most sociopaths, while all lack empathy, want to pay little or no cost for the things they want. He enjoyed violence and figured it was a part of life, the price he would, and did, eventually pay.

Excluding paranoid delusions and forensic profiler TV shows, most crimes are mundane and not very intelligent. Often stemming from a sense of dissatisfaction with our lives, we commit minor protests -- taking merchandise home from the freezer, fudging mileage reimbursements, and falsifying time cards -- to passively voice our resentment. When we see others who have to do much less to earn much more, we displace the anger to protect our egos, creating a self-imposed martyrdom: I suffer and, for that, I am unrecognized as a good person. The world owes me. When that narcissistic “specialness” is not recognized, the martyred person begins to take from others -- property, liberties, time...

But that sense of “deserving” more from the universe links back to a childhood lack of something which was desperately needed – affection, a sense of security the safety of boundaries between the self and other. Psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott said of childhood and adolescent delinquent behaviors, “The antisocial tendency implies hope. Lack of hope is the basic feature of the deprived child… ” The delinquent, Winnicott theorizes, is trying to claim something healthy, which is their right, and for which they have no means to express. If that desperate need is forfeited, the obedient child withdraws from the world, anger deeply internalized, and the mantra becomes: I must be wrong to want anything. The perpetually obedient child can be less healthy than the one who pushes back against the world—since that push is fueled by a perceived self worth defending.

From infancy to adulthood we learn the rules. Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development start at the most primitive level where we avoid negative consequences: If I do that, I will be punished. We mature to acknowledging our wish for acceptance within cultural norms: If I do that, others will think poorly of me. At the highest level, we have internalized those norms as a component of our self-image: If I do that, I will think poorly of myself. All those qualifiers are influenced by the matrix of factors that create the culture that surrounds each of us. How we see ourselves within, or excluded from, that culture determines our behavior.

Criminologist Lonnie Athens illustrates: “Ego-syntonic acts are acceptable to the ego and thereby congruent with an individual’s self-image. Thus, if violent crimes were in fact ego-dystonic, then the self-images of the violent criminal actors would be at sharp odds with their violent criminal actions... Although violent criminal acts may be ego-dystonic for psychiatrists, they are ego-syntonic for the people who commit them.”

Some people steal to eat, some steal to repair their injured self-images, but a degree of perceived personal gain is always present. In the most extreme examples, reality is not a factor. I once interviewed a man who believed his mother had been replaced by a CIA-designed android. He believed if he killed the fake mom, the real one would return. Crime only has to make sense to the person committing the act.

For years I ran a clinical team where a majority of our clients had seen the inside of a jail or prison cell -- some for arson, some for murder, but most criminal acts were severely disorganized attempts to survive life on the streets. A lot of my time was spent considering the differential between psychotic, criminal, and simply lousy behavior. While there is a degree of personal culpability with drug use, schizophrenia is not a lifestyle choice. A person with psychotic symptoms can be prompted by the internal stimuli of commanding voices. The paranoid ideation reflects a grandiosity that inverts the fear of being annihilated by the world. If the CIA is tracking a person and God is also giving him directives, how insignificant can that person be?

We all try to protect ourselves from that fear of annihilation, of being entirely wiped away by the world. That drive might also push a person to write a book about working-class, small-time criminals trying to maintain their self-respect.

In what feels like a past life, my pals and I performed the same miserable work as the narrator of this book. Six days a week, on the trucks or in the bar, we fantasized about not doing the work, not needing the work, and what we would do if we couldn’t get caught. The fantasy wasn’t about the criminal act, but about what it would afford, financially or emotionally. This book is about people who know they won’t leave a mark on the world, perceive few realistic options for change, but have an exquisite sense of having, somehow, been cheated.

To get our own back, we are sometimes willing to salt the earth we stand on and still hope something nurturing will grow.