this was written as a new's year's greeting for the Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis...

On Hope for the New Year

Year’s end,

all corners

of this floating world, swept.

Basho (1644-1694)

Shunryu Suzuki Roshi in a Zen lecture once said the Chinese character for “human” is two lines holding each other up and human existence demands this interdependence. Suzuki Roshi, like Winnicott, Bion, and many in our field, liked to make up his own words when those available didn’t carry enough associations. He spoke of “independency” to mean the non-duality of existence; we are simultaneously independent and totally dependent upon each other. He also alluded to the “independency” of good and bad/light and dark. A lot of Zen writings sound dark, but it’s the dark stuff that contains hope and a possibility of lightness. Both exist together and cannot exist without each other.

As we close in on the start of 2024, it’s difficult to not think of all the injustices in the world. We don’t have to look hard to conclude Things don’t look good. And we wouldn’t be wrong. We have a lot to do.

But maybe our responsibility, especially now, is to maintain hope for each other and ourselves. Maybe our job is to hold each other up the best we can, and, in this, we can find our own supports.

At the Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis, we hope to continue as a community that supports itself by supporting each other. We don’t know exactly what the universe has on order, but we’re hopeful for what we have planned and are planning for the coming year.

Of this hopefulness, I think of my old pit bull. No matter the day or the situation, her mantra remained: “I don’t know what’s coming, but it’s going to be great! … A snack, a nap, maybe I run around in circles. I don’t know, but it’ll be great!” Her disappointments would be intense, but always momentary. She always came back to the anticipation and appreciation of something in the world.

gruel heaped

in a perfect bowl—

sunlight of New Year’s Day

Joso (1662-1704)

My wish for 2024 is that we can continue the hard work which the world demands of us, keep supporting each other best we can, and remain as hopeful as pit bulls.

Thank you for all being a part of CCP.

Happy New Year.

Zak Mucha, LCSW

President, Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis

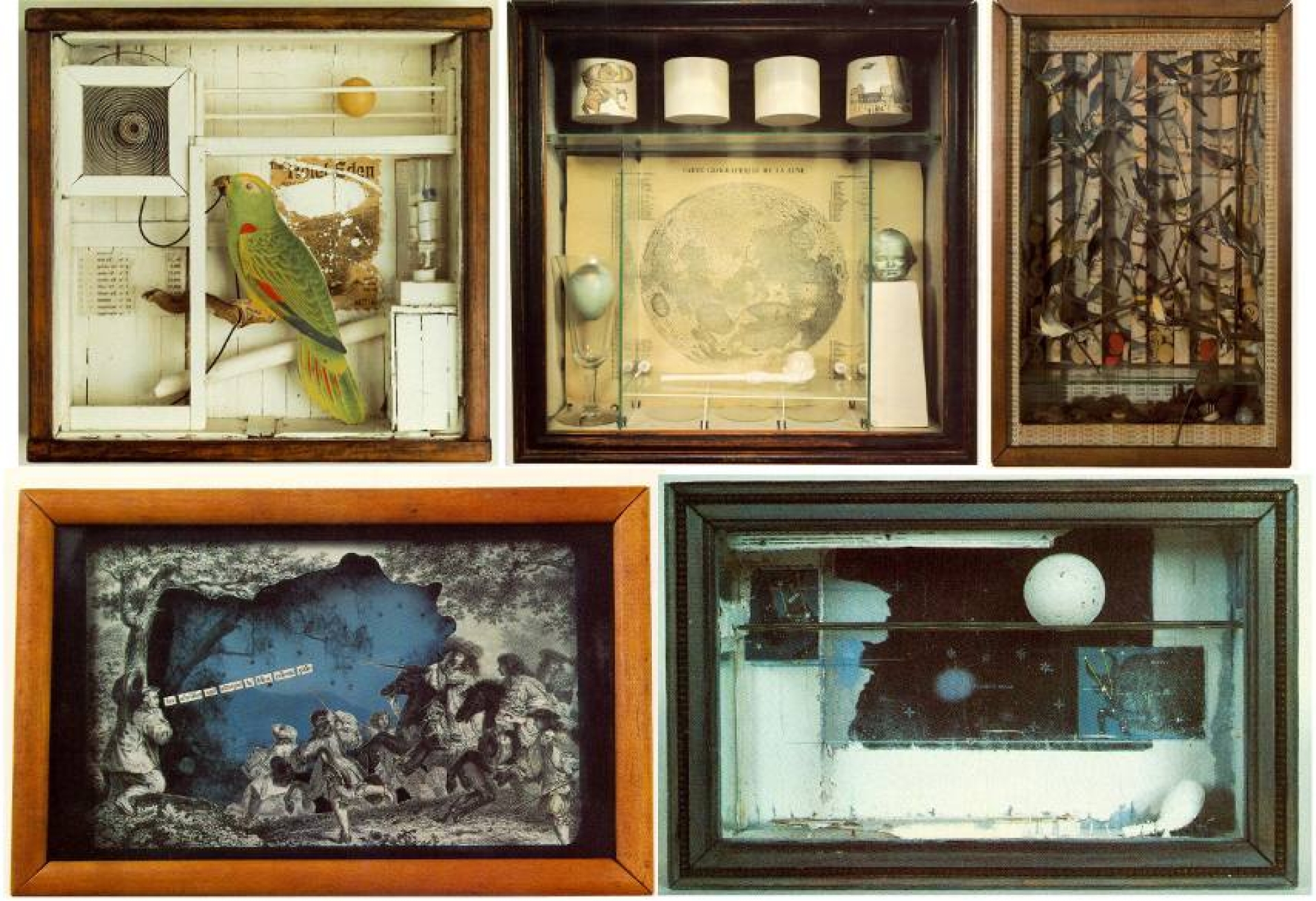

Joseph Cornell

Lewis Mumford wrote: “All art is a sort of hidden biography. The problem of the painter is to tell what he knows and feels in such a form that he still, as it were, keeps his secrets.”

The artist Joseph Cornell had to create his own world to keep his secrets. He lived a childhood of rich imagination and severe, polite isolation. His sister recalled an adolescent Cornell waking her in the middle of the night, “He was in the grips of a panic from the sense of infinitude and the vastness of space as he was becoming aware of it from studying astronomy.”

As an adult, he never moved out of his mother’s house in Queens. Cornell sold textiles door-to-door in the city and turned the basement into his art studio. He took discarded bits and bobs found on his searches through Times Square bookstores and junk shops, creating shadow boxes of paper birds and soap bubbles, giving titles to his internal narratives of old hotels and lost children. When he couldn’t find appropriate boxes for his found items, he built his own, aging them until they seemed found also, they became natural containers for the collections inside. Random chance guided his searches. He would reassemble his found items like he was building poems, juxtaposing images on instinct, linking ideas for others to make their own associations.

Cornell’s collages and boxes are akin to the early stage of dream work before interpretations are applied. In his work is the unnamable, the non-chronological connections between all things -- the idea that, if there is a god of some kind, it is beyond any description. Any meaning we place on it can only be mistranslated as the shift to language changes the meaning of the images. Cornell tried to explain a world for which he had no hard evidence and no explanations.

The day he died, Joseph Cornell told his sister over the phone: “I wish I had not been so reserved.”

The Ambulatorium

I had never written poetry until something clicked as I walked from my analyst’s office. Since I was 18 years old, I wrote, but was never brave enough to try poetry. I made some notes that day and kept playing with the words. This felt like getting hit in the head with a can of peaches only to wake up and feel like I can play the piano.

In the best moments, psychoanalysis can be described much like the poet Charles Simic defined a poem as “… an attempt at self-recovery, self-recognition, self-remembering, the marvel of being again… A poem is a piece of the unutterable whole.”

Psychoanalysis is weird and can be terrifying, but a fifty-minute session that surprises both the therapist and patient becomes a poem in this way and the arc of a therapeutic relationship becomes a glimpse of that unutterable whole of one’s self. Like analysis, writing poetry is this effort, for me, of trying to be as precise as possible while trying to figure out what it is I’m trying to say.

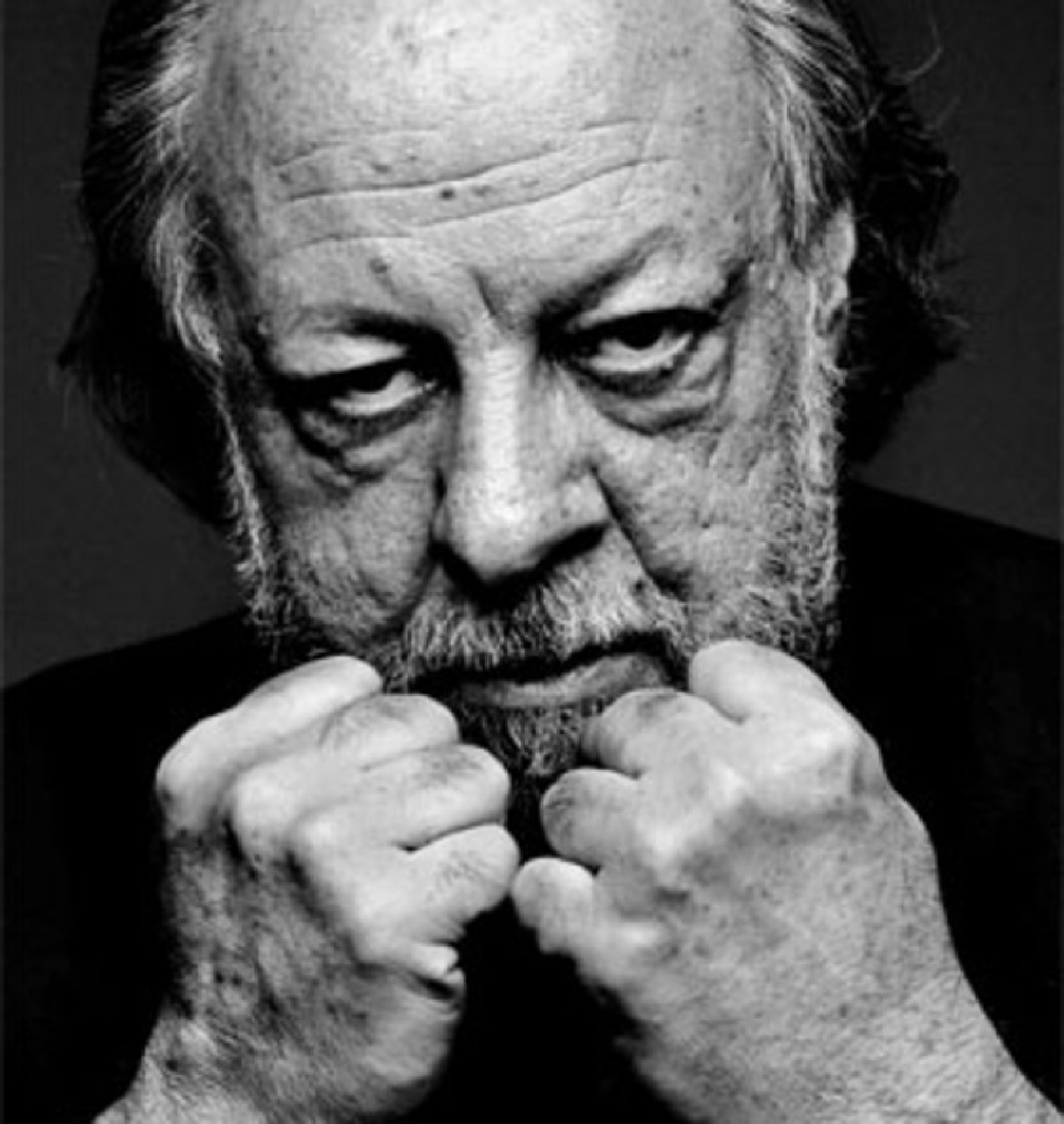

As a kid, I was creeped out by the magicians who acted as if they had ‘special powers.’ I wanted to be fooled by the tricks, not by the 1970s leotards and sequins. I wanted them to look like guys who could be working normal jobs or selling air conditioner boxes filled with bricks at the off-ramp by I-94 and Halsted.

Oh, Lucky Me

(for Ricky Jay)

10 years old he switched the Colgate

and Brylcreem, proud of the simple

subterfuge between cabinet and sink,

seeing the first signals of something

(that knowledge existed between gestures)

uncertain and disappointed to be

the son of obedient routine.

To learn how to see what others couldn’t

he sought out Catskills magicians with names

once chopped, rounded, and Americanized

by Ellis Island lines, names refracted

again balancing the urge to stand

apart and remain within the crowd.

To see how hands could move he sought out

Vegas sharps who performed in silence

with names meant to be forgotten.

He created séances of mirrors

to slow time between bright spotlight gestures,

watched his own hands from every angle

until they belonged to a stranger.

One morning he woke up ambidextrous.

He learned not to look at the ghosts of his

hands unless he wanted others to see.

He disappeared himself, looking for a

way to master that invisible gap

between people where each space signified

possible truth between words. He wanted

to find the gap where nothing happens and

nothing is said. He wouldn’t talk about

his parents, but his sister was okay.

I saw him first at a card table

in a Mamet movie, lugubrious

and hooded when calling the last hand in

the United States of Kiss-My-Ass.

He said the lines right, dead bored and angry:

“What is this ‘marker’? Where are you from?”

Not stomping along with the beat, drumming

a bit ahead: “Who is this broad?”

or dragging behind: “Club flush. You owe me

six thousand dollars. Thank you very much.

Next case.”

Dismayed to see him giggling with talk show

hosts, I expected a stone-faced disruption of

the showbiz mutual non-aggression pact.

I wanted the Jungian shadow of

every magician, a criminal

carrying the fantasied grace and the

palpable rage of a child ignored

and a fake name so obvious it was

more real than birth.

He built his library and a thug took it --

dismissive of the cup-and-ball trick

depicted in hieroglyphics and the

history of the world infused with fools

or tricksters since the first owl-faced God

scratched on rock – a foreclosed car lot cleared

without a drop of sweat, just the brute force

of a world where math is not memory,

but the gravity of capitalism

where there is no illusion and no grace.

He held a bemused tolerance for the

year he was born and the years in which he

stood. The name discarded, a point of pride --

like being born in a car wreck.

Against that sadness, being outside time

was another trick to save himself.

A sold-out run at the Old Vic, the true

sharps never came backstage, but sat with their

new wives just off the center aisles.

He breezed through the differences between a

Vegas shuffle, a gin rummy shuffle,

and a child’s two-palmed scramble to always

find, as he said: “Oh, lucky me,”

the ace of spades yet again.

He quoted Seneca, Villon, and Shaw

between dead cuts, bottom and second deals:

“Every profession is a conspiracy against the laity.”

Audience members at each elbow he

made the queens and aces appear at will.

He simply knew where they were at all times.

A woman from the BBC told once

of his truculent participation

in documenting his own life,

(he refused to perform for her cameras)

making her job more difficult than it need be.

Lunch in LA, he chose the restaurant,

pissed her off all day, and then, as the

waiter took the laminated menus away

from the glaring sun of the corner booth,

made a block of ice appear between them.

She didn’t know why she burst into tears.

She asked: “Why did you do this to me?”

He shrugged: “I lie for a living.”

(originally published in Tuck Magazine, later published in Shadow Box)

On Paranormal TV

I’ve been watching The Dead Files, a paranormal reality TV show where a retired NYC homicide cop and an empath investigate haunted houses. The cop interviews the family and looks into the property history while the empath walks through the house alone (with two cameramen and a crew) interacting with whatever spirits inhabit the place. They get together at the end and present their findings to the family.

As the show Dateline (which mostly features men who would rather commit murder than go through a divorce) may present a vicarious entertainment for homicidal thoughts about one’s family and friends, Dead Files can be the fulfillment of a wish going back to childhood, having someone who could explain why the house feels so unsafe. Maybe it’s a common fantasy that trusted experts could enter a home, find the evil thing, and then, via salt, smudge, or exorcism, rid us all of the bad feelings.

The cop and the empath investigate the seen and unseen worlds and it’s all edited down to the regularity and predictability of Law and Order or CSI episodes. It’s a sort of reality TV metaphysics--an attempt to observe the unobservable to make some sense of being. Like all desires (no matter if they’re concrete or abstract), it’s ultimately unsatisfying, which is why we watch again and again.

There’s a similar show on another platform where it’s Chicago cops performing paranormal investigations. It’s pretty much what you’d expect – when the spirits don’t materialize, these guys start yelling, challenging the manhood of the dead and daring them to come back from the bardo. I stopped watching before someone got killed.

*

collage/ bridgette bramlage

Friday, 15 September 2023 15:09collage/ bridgette bramlage

I sometimes catch bits and pieces of the progress in my wife’s studio. She’s an artist. She has stacks of magazine and books from the first half of the 20th century all around the house and sifts through them with a patience created by a sense of wonder. She cuts up tarot and Loteria cards, books of old magic tricks, cigarette advertisements, and glossies of Detroit muscle cars, looking for what they might be saying to each other. I’ve watched her work change over the years, but what I always see is the unconscious process where images collate and come together, allowing a conversation to begin. Parallels and links emerge among images – sometimes a cosmology of shape and line without human signifiers.

In Dime-Store Alchemy, Charles Simic wrote of Joseph Cornell’s collages and assemblages:

“You don’t make art, you find it. You accept everything as its material. Schwitters collected scraps of conversation, newspaper cutting for his poems. Eliot’s Waste Land is collage and so are Pound’s Cantos… The collage technique, that art of reassembling fragments of preexisting images in such a way as to form a new image, is the most important innovation in the art of this century. Found objects, chance creations, ready-mades (mass-produced items promoted into art objects) abolish the separation between art and life. The commonplace is miraculous if rightly seen, if recognized.”

The process reminds me of therapy sessions where both the patient and analyst are both surprised by what came up by the end of the hour. Collage, like a conversation of unedited associations, allows us to catch glimpses and references of our associations that build our worlds. A meaning begins to hint at itself.

Watching my wife piece together her work, I add two haikus:

a story found in scraps

cut and pasted from

thoughts untended

a shape centered on

white paper hints at past and

future images

***

on Labor Day (and crime)

Saturday, 02 September 2023 11:03(This was an introduction to a re-printing of an old novel, The Heavyweight Champion of Nothing, about working class guys committing crimes to get back at their boss)

*

The motivation for most criminal acts can be summarized as: “I saw something I wanted, so I took it.” In general, people go to jail for two reasons: They do not consider incarceration a deterrent and/or they don’t believe they’ll get caught in the first place.

Jacques Mesrine, proudly classified as Public Enemy #1 in France and Canada fifty years ago, was willing to pay the price for what he wanted. Throughout his autobiography, which has to be taken with many grains of salt, he did frequently cite his wish to die rather than be denied. So he committed daylight bank robberies, sometimes twice a day; engineered prison escapes, once taking a judge hostage and another time, returning to the prison to prompt a gunfight at the gate; during one late-night apartment burglary in Paris where the safecracker’s drill broke, Mesrine went down the street and burglarized a hardware store for more drills and then returned to the first burglary in progress. Mesrine was the rare outlier as most sociopaths, while all lack empathy, want to pay little or no cost for the things they want. He enjoyed violence and figured it was a part of life, the price he would, and did, eventually pay.

Excluding paranoid delusions and forensic profiler TV shows, most crimes are mundane and not very intelligent. Often stemming from a sense of dissatisfaction with our lives, we commit minor protests -- taking merchandise home from the freezer, fudging mileage reimbursements, and falsifying time cards -- to passively voice our resentment. When we see others who have to do much less to earn much more, we displace the anger to protect our egos, creating a self-imposed martyrdom: I suffer and, for that, I am unrecognized as a good person. The world owes me. When that narcissistic “specialness” is not recognized, the martyred person begins to take from others -- property, liberties, time...

But that sense of “deserving” more from the universe links back to a childhood lack of something which was desperately needed – affection, a sense of security the safety of boundaries between the self and other. Psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott said of childhood and adolescent delinquent behaviors, “The antisocial tendency implies hope. Lack of hope is the basic feature of the deprived child… ” The delinquent, Winnicott theorizes, is trying to claim something healthy, which is their right, and for which they have no means to express. If that desperate need is forfeited, the obedient child withdraws from the world, anger deeply internalized, and the mantra becomes: I must be wrong to want anything. The perpetually obedient child can be less healthy than the one who pushes back against the world—since that push is fueled by a perceived self worth defending.

From infancy to adulthood we learn the rules. Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development start at the most primitive level where we avoid negative consequences: If I do that, I will be punished. We mature to acknowledging our wish for acceptance within cultural norms: If I do that, others will think poorly of me. At the highest level, we have internalized those norms as a component of our self-image: If I do that, I will think poorly of myself. All those qualifiers are influenced by the matrix of factors that create the culture that surrounds each of us. How we see ourselves within, or excluded from, that culture determines our behavior.

Criminologist Lonnie Athens illustrates: “Ego-syntonic acts are acceptable to the ego and thereby congruent with an individual’s self-image. Thus, if violent crimes were in fact ego-dystonic, then the self-images of the violent criminal actors would be at sharp odds with their violent criminal actions... Although violent criminal acts may be ego-dystonic for psychiatrists, they are ego-syntonic for the people who commit them.”

Some people steal to eat, some steal to repair their injured self-images, but a degree of perceived personal gain is always present. In the most extreme examples, reality is not a factor. I once interviewed a man who believed his mother had been replaced by a CIA-designed android. He believed if he killed the fake mom, the real one would return. Crime only has to make sense to the person committing the act.

For years I ran a clinical team where a majority of our clients had seen the inside of a jail or prison cell -- some for arson, some for murder, but most criminal acts were severely disorganized attempts to survive life on the streets. A lot of my time was spent considering the differential between psychotic, criminal, and simply lousy behavior. While there is a degree of personal culpability with drug use, schizophrenia is not a lifestyle choice. A person with psychotic symptoms can be prompted by the internal stimuli of commanding voices. The paranoid ideation reflects a grandiosity that inverts the fear of being annihilated by the world. If the CIA is tracking a person and God is also giving him directives, how insignificant can that person be?

We all try to protect ourselves from that fear of annihilation, of being entirely wiped away by the world. That drive might also push a person to write a book about working-class, small-time criminals trying to maintain their self-respect.

In what feels like a past life, my pals and I performed the same miserable work as the narrator of this book. Six days a week, on the trucks or in the bar, we fantasized about not doing the work, not needing the work, and what we would do if we couldn’t get caught. The fantasy wasn’t about the criminal act, but about what it would afford, financially or emotionally. This book is about people who know they won’t leave a mark on the world, perceive few realistic options for change, but have an exquisite sense of having, somehow, been cheated.

To get our own back, we are sometimes willing to salt the earth we stand on and still hope something nurturing will grow.

in memory of sandra ullmann

Tuesday, 01 August 2023 11:22Psychoanalyst, photographer and teacher, Sandra Ullmann, died earlier this year. What now feels like a long time ago, I attended her group consultations where she provided, for me, a gentle introduction to psychoanalysis. I needed it.

Painting with John

Wednesday, 19 July 2023 14:06Painting with John is a TV show on its third season. The host, musician John Lurie, who is also a painter, was first presented in media shorthand as the anti-Bob Ross and this was a show that didn't teach you how to paint.